Can Communicating the Benefits of Novel Ecosystem Restoration Techniques Promote Climate Change Literacy and Action?

Learning about how restoration projects can benefit their communities can inspire people to take more than just the usual, low-effort actions meant to address climate change. Read about my online workshop held in fulfillment of the UW PCC Graduate Certificate in Climate Science.

Written by James Lee

I’m from a place in the San Francisco Bay Area where ecosystem restoration is talked about a lot. Nine years ago, my friends and I worked to stop the development of over 10,000 luxury housing units on about 1,400 acres of restorable wetlands. When I came to the UW’s School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, I knew I wanted to conduct research in wetland ecosystems and be involved with a restoration project. I eventually became a research lead for an artificial “floating wetlands” project deployed in the Lower Duwamish River in the summers of 2019 and 2020.

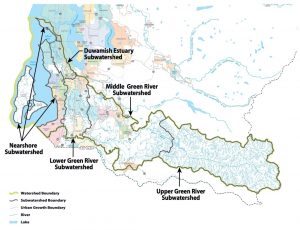

The Lower Duwamish River

South Seattle’s heavily industrialized Lower Duwamish River (LDR) was designated an EPA Superfund site about twenty years ago. Communities living in the area continue to be affected by the legacy of settler-colonialism, redlining, and generations of subsequent damage to the environment and public health. Even before Superfund designation, the Duwamish, Suquamish, and Muckleshoot Tribes and community groups in South Seattle have been continuously working to reverse or at least mitigate this damage by restoring portions of the riparian corridor and nearby green spaces.

For communities living near the LDR in the Duwamish Valley, climate change adds a layer of complexity to current efforts to address historic and ongoing environmental damage. There are various ecosystem restoration efforts being implemented in the area to address this damage, and these restoration projects are often billed as being necessary to prepare for climate change as well. But can such projects really shield communities from the worst climate change impacts in a place like the LDR where the heavily urbanized and modified nature of the shoreline limits opportunities for restoration? In such places, novel ecosystem restoration techniques, or NERTs, may be a way to expand options for improving ecosystem function and community health, but even practitioners of environmental restoration often have a narrow definition of the kinds of restoration that are desirable and successful.

How I Got Involved

During my research, community members articulated to me that while I and my research team might think a floating wetlands project was interesting and potentially beneficial for the river and for nearby communities, Duwamish Valley residents might be more interested in prioritizing other actions to benefit the community besides an obscure novel ecosystem restoration technique (NERT), particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic which has exacerbated existing societal inequities.

Many of these inequities have clear connections to climate change and other problems that restoration projects are meant to tackle, and many community advocates are articulating these connections themselves. However, topics like NERTs or other creative projects meant to help people prepare for climate change may not be of immediate salience to Duwamish Valley residents, particularly if they originate from academia and not from the community itself.

Knowing this, I was no longer certain my research would provide relevant benefits to Duwamish Valley residents, and I wanted to give back to the community in some other way. One recommendation from a community member was to share what I had done and learned in an online workshop, but how could I make sure that attending this workshop would benefit someone? Specifically, I wondered:

- “Would learning about novel ecosystem restoration techniques change people’s understanding of climate change impacts salient to their community?”

- “Would learning about novel ecosystem restoration techniques make people any more or less receptive to the use of non-traditional restoration techniques?”

- “Would learning about novel ecosystem restoration techniques change the level of motivation and inspiration people feel in taking action on climate change impacts salient to their community?”

I worked with Dr. Miriam Bertram, Assistant Director of the Program on Climate Change, to settle upon these three research questions and design a climate communication project that could answer them.

The Workshop

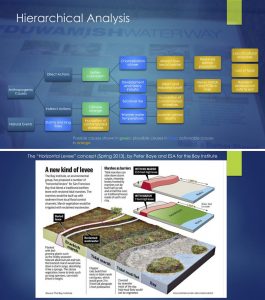

To answer these questions, I held a workshop in which I gave a presentation that provided an overview of the science behind climate change, a history of the Duwamish River, and the impacts of settler-colonialism on the river’s ecosystem function. The presentation also described climate change impacts most likely to be experienced by residents of Washington State, and especially by communities near the Duwamish River. I then spoke about the floating wetlands project before ending with an overview of how ecosystem restoration projects can help communities be more able to withstand the impacts of climate change.

Besides my own past experience with and research into climate change, ecosystem restoration, and the Lower Duwamish River, I drew from what I learned in Dr. Curtis Deutsch’s class on climate and global carbon cycling for my workshop, as well as from “No Time to Waste,” the UW Climate Impact Group’s 2019 report on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 ºC. After the event, a PDF file of the slide presentation was made publicly available on Github.

I had participants fill out two surveys before and after the workshop to determine any shifts in attitude before and after the presentation. For Likert scale responses, which is where people mark how much they agree or disagree with a statement, I used statistical analysis to quantify changes in attitude. I used qualitative analysis software to identify shifts in themes and attitudes in answers to free-response questions. I then assessed how my research questions were answered, if at all, by these changes.

What Did I Find Out?

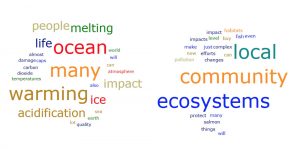

I was excited to find that my data supported the idea that learning about novel ecosystem restoration techniques (NERTs) did increase workshop attendees’ understanding of climate change impacts, as well as their receptiveness to the use of non-traditional restoration techniques! In particular, workshop participants shifted from talking about climate change in general terms related to its physical causes to talking more specifically about how climate change might impact them at the scale of their own communities. Additionally, there was not just a measurable shift but also a clear expansion in participants’ thinking about the kinds of ecosystem restoration projects that they thought were possible and desirable.

The data didn’t support the idea that learning about NERTs would increase the level of motivation and inspiration people feel in taking action on climate change impacts salient to their community. However, that was because everyone who chose to attend the workshop had already identified themselves as being highly motivated to take action.

Still, after the workshop there was a significant increase in agreement with the statement: “I know what specific actions my community can take to prepare for the impacts of climate change.” Many people who are highly motivated to take action on climate change often don’t know what to do, beyond low-effort modes of engagement with the political process such as signing online petitions, sending letters to elected officials, and attending protests. After the workshop, participants were able to express a much broader range of tools they could use and actions they could take on climate change, and they were thinking more about the role of community needs and priorities in climate adaptation too. In the survey’s free responses, occurrences of action-taking language more than tripled after the workshop!

Reflections on Positionality and Research Outcomes

As a graduate student who is neither a South Seattle resident nor a member of one of the many underrepresented minority groups in the area, it was very clear to me that a power dynamic existed between myself and the community in which I was intending to conduct my research, and that I needed to practice reflexivity. Montana, et al. (2020) provide multiple definitions of reflexivity, including but not limited to the examination of one’s own identity, intentions, and actions. Reflexivity can also mean analyzing the relationships that one fosters in the communities where they conduct their work.

While I was completing the floating wetlands project, community members made it abundantly clear to myself and my colleagues that Duwamish Valley communities are underserved despite being over-researched for their expertise, and that research conducted in their communities needed to be relevant to community priorities and provide adequate compensation for community members’ time and knowledge to ensure that more people than just those who are conducting the research can receive tangible benefits.

This feedback had a major influence on this study. Initially, my intent was to engage with community experts to help shape my research questions, the design of the survey and the workshop presentation. However, after receiving feedback I did not feel it was ethical to enlist a community member for hours of unpaid collaborative work when I could not adequately compensate them for their time. Instead, I chose to take on board the feedback I had already received from key informants and other community members in my previous research and to use that to inform both the content of my workshop, my target audience, and the mode of compensation for community members’ time. Ultimately, I decided to spend all of the limited funds I had personally allocated for this study on direct compensation for participants.

Residents of the Duwamish Valley are not unique in their ability to learn about climate change. However, they are distinct in that they are directly impacted by environmental inequities in ways that other communities in Seattle are not. Although there are some similarities among the participants in this project, it is likely that being aware of such impacts meant that Duwamish Valley community members were already more primed to understand the impacts of climate change and were more motivated to take action. These assumptions cannot be supported with the limited data available in this study, but it could serve as an interesting foundation for future studies on climate change communication.

I believe my results support the idea that targeted engagement and tailored communication about novel ecosystem restoration techniques can indeed not only improve people’s knowledge of climate science and ecosystem restoration, but also broaden their thinking on climate change by making the science relevant to each community’s unique contexts. It can also make people more receptive to creative, novel approaches to restoration, which will become ever more vital as the impacts of climate change continue to compound.

Presenting climate change through the lens of restoration and restoration techniques can shift people’s thinking on climate change so that their attitude on the subject is more action-oriented, creative, and positive. Fostering these attitudes through effective communication tools will continue to be vital in ensuring community resiliency, and swift, novel, and effective action when it comes to climate change.

James Lee is a soon-to-be graduate of the UW School of Marine and Environmental Affairs (SMEA) and completed this project for the Graduate Certificate in Climate Science. His master’s capstone project focused on the use of novel ecosystem restoration techniques in South Seattle’s Lower Duwamish River, and he and his research team used that firsthand experience as a case study in a report on policy perspectives and recommendations for ecosystem restoration and community health in the Duwamish Valley. As outgoing editor-in-chief of Currents, SMEA’s blog, he also has a strong interest in science communication and wanted to give back to the residents of the area in which he conducted his research by providing an informative workshop on climate change, and on what people can do at the local level to prepare for its impacts. Documents related to this project have been made publicly available on Github, and you can get in touch with James on Twitter or by email.