Community-engaged climate adaptation: partnering with Search and Rescue in Northwest Iñupiaq Alaska

by Charlie Hahn (Anthropology), Chase Puentes (Geography) and Ellen Koukel (Atmospheric Sciences)

As part of their graduate research, Charlie, Chase, and Ellen worked collaboratively with a volunteer search and rescue group from the Iñupiaq village of Kivalina, Alaska. Their projects aim to build on the latest in climate science to produce knowledge relevant to both the academy and the community. This past winter, PCC Climate Solutions* funding allowed the students to travel to Kivalina to discuss with their collaborators proposals for better applying their research to community climate adaptation needs. Despite travel difficulties due to a strong winter storm, the team managed to workshop their proposals regarding a community sea ice monitoring portal, a safety focused digital storytelling archive, and a first responder training for search and rescue personnel. This trip proved critical in making concrete the more applied dimensions of their projects, an essential step in the continuously iterative process that is community-engaged adaptation research.

“I was right there across the lagoon, just past the airport,” one hunter recalls. “I had a phone and was using the GPS maps on my phone, but I couldn’t see. Eventually I got through to Reppi and had people come find me. At one point they were just a few feet away but we couldn’t see or hear each other it was blowing so bad. They end up finding me and got me back home.”

It’s mid-December and our team of UW graduate students is gathered at the community center in Kivalina, a 500-person Iñupiaq community in Northwest Alaska. We’ve just shared a meal of homemade chili, baked fish, and potato salad and are discussing stories of past search and rescue events with several core volunteers from Kivalina’s Volunteer Search and Rescue organization (KVL-SAR). Outside, the remnants of a winter storm are blowing, though not quite as severe as what the hunter describes above. And everyone was still thinking about the historic typhoon Merbok which just a month earlier had crashed into western Alaska causing widespread damage to villages across the region.

The group, led by Replogle “Reppi” Swan Sr. (KVL-SAR President) and Colleen Swan (KVL-SAR Administrator) discusses priorities for SAR capacity building and new potential collaborative research projects. These include: outfitting first responders with GPS/messaging devices to improve rescue communication, co-hosting a wilderness first responder training for SAR responders and community members, developing an audio/video archive of SAR response stories for hunter safety and training purposes, and expanding our work on local sea-ice monitoring and forecasting through social media.

Our team, consisting of graduate students from Atmospheric Sciences, Geography, and Anthropology, has been working with Kivalina for the past three years to scale climate tools and technologies to be useful at the community level (https://www.kvlseaice.org/). The use of community observers has become widespread within Arctic environmental research, a community increasingly invested in the “co-production” of knowledge (Druckenmiller 2022). By centering the practical and material concerns of our community partners in the formation of our research questions we hope not only to co-produce knowledge but also action. Drawing on years of relationship building and collaborative ethnography in Kivalina, our team has partnered with KVL-SAR as a key vehicle for community-scaled climate knowledge production and hazard response.

In this way, all of our modest attempts at collaborative capacity building for KVL-SAR programs are also research endeavors. The projects we’ve co-created involve the development of new theory and toolsets for climate hazard GIS mapping, models for analyzing sea-ice dynamics like lead formation and breakup at small scales, and the ethnographic understanding of Arctic Indigenous adaptive priorities.

Hunting and fishing and Search and Rescue in the rapidly changing Arctic

A few hours before our meeting with KVL-SAR, a group of friends and collaborators took us ice fishing just a few miles out of town up the Wulik River. Using a gas powered auger, Reppi drilled a few holes in the ice and we dropped our lures into the water below, methodically jigging. The fish were slow to bite, but eventually our luck improved and our group was pulling fish out of the river, one after another. After a few hours later we had managed to amass a small pile of grayling and Dolly Varden trout—a species of Arctic char.

“Almost half a [gunny] sack!” our friend Ahquk Wesley congratulates us–only half-jokingly.

That day on the river our fishing party discussed seeing more instances of open (non-frozen) water, even in the heart of winter. This is unusual compared to the past, where the river would freeze almost completely for most of the winter and into spring. While Kivalina hunters are experts at safe travel on land and ice, the pace of environmental change produces more and more uncertainty, and therefore hazards throughout the land and seascape.

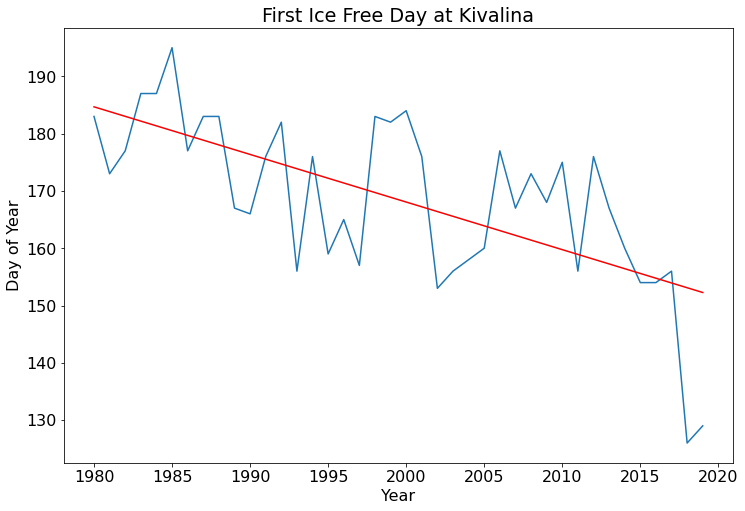

With regard to changes to river ice, hunters can often navigate around these open spots, as dangerous as they are. But adapting to declining sea ice has been far more difficult. Historically, the sea ice off the coast of Kivalina would remain thick and fast far into the spring, providing a stable platform for traditional bowhead whale hunting. Today, a spring with thick sea ice is an anomaly (see fig. 1), and thus the community is faced with hunting either on thin ice or by boat in open water. The latter option is a wholly new mode of hunting that presents new challenges both in terms of acquiring larger boats and other expensive equipment to mitigate newfound risks and uncertainties.

For Kivalina and other Alaska Native and Arctic Indigenous people, hunting and fishing are central to the networks of care that support community wellbeing and flourishing (Griffin 2020). In the context of the rapidly changing environment, formalized SAR organizations are essential for responding to the increase in uncertainty and the associated hazards while hunting and traveling on the land (see Clark et al. 2016), and therefore to community resilience more broadly. By locating knowledge production within such organizations, our research is more likely to address local concerns and adaptive priorities.

Community engagements in Arctic scientific research

The Arctic and sub-Arctic have long been sites of encounter between Native communities and non-Native scientists who have often turned to Indigenous knowledge for both practical and scientific purposes. Despite this history of engagement, early scientific endeavors to the North essentially mirrored the material colonization of land and resources that was occurring simultaneously: Indigenous knowledge of the land and environment was bought, stolen, or otherwise extracted by explorers and scientists while communities gained little (Cruikshank 2007; see also Smith 2012). However, in the last few decades scientists have begun attempting to build more equal relationships with communities.

Responding to criticisms of research from both academia and communities themselves, a recent focus on community-engaged methods has centered on the concept of “co-production” (Druckenmiller 2022). This model moves beyond merely recognizing the validity of local knowledge towards attempting to address research questions and concrete concerns of Indigenous communities and institutions themselves. The building of long-term relationships, developing advisory councils and other mechanisms of researcher accountability, and hosting iterative research design or analysis workshops are all components of this emerging approach. Such methods have the potential to “put people first” in Arctic climate change research (Huntington et al. 2019).

Our work is co-directed by leaders of KVL-SAR and the City of Kivalina and emerged from Reppi and Colleen’s ten-year relationship with P. Joshua Griffin, assistant professor in Marine and Environmental Affairs and American Indian Studies here at UW. As a whole, the project seeks to activate climate science in support of community-scale responses and adaptation priorities. Indigenous feminist scholar Kim TallBear envisions a research process grounded in “overlapping respective intellectual, ethical, and institution building projects” and that “share[s] goals and desires while staying engaged in critical conversation and producing new knowledge and insights” (2014). As such, our research works through engaged methods to also address the scholarly and scientific debates within the university and our professional communities as atmospheric scientists, geographers, and anthropologists.

Works cited:

Clark, Dylan G., James D. Ford, Tristan Pearce, and Lea Berrang-Ford. 2016. “Vulnerability to Unintentional Injuries Associated with Land-Use Activities and Search and Rescue in Nunavut, Canada.” Social Science & Medicine 169 (November): 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.026.

Cruikshank, Julie. 2007. Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. UBC Press.

Druckenmiller, Matthew. 2022. “Co-Production of Knowledge in Arctic Research: Reconsidering and Reorienting Amidst the Navigating the New Arctic Initiative.” Oceanography, 189–91. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2022.134.

Griffin, P. Joshua. 2020. “Pacing Climate Precarity: Food, Care and Sovereignty in Iñupiaq Alaska.” Medical Anthropology 39 (4): 333–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2019.1643854.

Huntington, Henry P., Mark Carey, Charlene Apok, Bruce C. Forbes, Shari Fox, Lene K. Holm, Aitalina Ivanova, Jacob Jaypoody, George Noongwook, and Florian Stammler. 2019. “Climate Change in Context: Putting People First in the Arctic.” Regional Environmental Change 19 (4): 1217–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01478-8.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd edition. London: Zed Books.

TallBear, Kim. 2014. “Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry.” Journal of Research Practice 10 (2): N17–N17.

*Climate Solutions projects such as this are generously supported by donors to the Program on Climate Change Graduate Education Fund, which empowers graduate students in applying their climate-science knowledge to solutions-based projects, climate communication projects, capstone programs, and outreach efforts with community organizations and partners to help them gain experience outside academia.”