Improving park access and health co-benefits in Tacoma using a “Green Schoolyards” approach

By Nolan Kitts

Who doesn’t love a good park? Especially in urban areas, public green spaces give us opportunities to move around outside, find some quiet, and enjoy a more natural setting. Researchers have established many benefits of urban park access, from increasing physical activity to improving mental health. With a changing climate, urban parks have become even more critical. Park trees can decrease the impact of “urban heat islands” through evapotranspiration and providing shade. By reducing impervious surfaces, urban green spaces can also help absorb more runoff from extreme rainfall events.

Unfortunately, only some have great access to urban parks. According to the Trust for Public Land (TPL), over 65,000 Tacoma residents (31%) live more than a ten-minute walk from urban green space. This is the most significant park access gap in Washington. As you can imagine, the solution isn’t as simple as making a new park out of nowhere… That’s why the Trust for Public Land has teamed up with Metro Parks Tacoma and Tacoma Public Schools to transform five schoolyards into “Green Schoolyards.” This project will turn blacktop playgrounds into green community parks open to the public outside of school hours.

What did we do?

For my ACORN volunteer project, I worked with Kathleen Wolf from UW Nature and Health and researchers from Seattle Children’s Hospital and The Trust for Public Land to understand how these new green schoolyards improve park access and physical activity within the “Ten-Minute Walk Zone.”

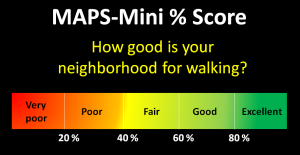

We started by auditing the streetscape within a ten-minute walk of three Tacoma Schools. Two schools (Mann Elementary and Whitman Elementary) are slated to get a schoolyard upgrade through the TPL project. The third School (Browns Point Elementary) was located in a more affluent neighborhood in northeast Tacoma and had recently renovated its schoolyard. To understand the physical streetscape around these schools, we used a tool called Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes-Mini (MAPS-Mini). MAPS-Mini uses 15 qualitative and quantitative measures of neighborhood walkability, including counts of crosswalks, street trees, tripping hazards, and street lights. We used the MAPS-Mini protocol to randomly sample street segments within the ten-minute walk zone of all three schools.

In addition to MAPS-Mini, a focused assessment of walking infrastructure on a specific street segment, we collected Walk Scores from walkscores.com, an alternate measure of walkability related to a given location’s distance to businesses and public amenities. Where MAPS-Mini scores might quantify the ease with which residents can move throughout their neighborhood, Walk Scores might point to factors that get residents outside and walking in the first place. We were interested in seeing if there is a relationship between MAPS-Mini scores and Walk Scores and if this additional measurement allows us to assess further the walkability of the 10-minute walk area surrounding the new Green Schoolyards in Tacoma.

We found that the two test schools (Mann and Whitman) generally had higher walk scores but lower MAPS-Mini scores than the control (Browns Point). This suggests these neighborhoods have more amenities but a less appealing/pedestrian-friendly streetscape. This is an important finding because the Green Schoolyards Project depends on a good pedestrian environment in the surrounding neighborhood.

Last summer, Bernadette Labuguen (UW Architecture and Landscape Architecture), another grad student ACORN volunteer, helped the research team collect data on physical activity at schoolyards before their renovation. This data will be used in a before/after study to directly measure the impacts of Green Schoolyards on improving activity and associated health outcomes.

How did it go?

Working on this project for the last year and a half has been very enriching. I saw firsthand how unique collaborations like this one between researchers, city government, and non-profits could lead to real community-driven change.

The Trust for Public Land plans to complete the schoolyard transformations later this year, so this project was only the beginning of an effort to monitor the neighborhood changes these new green spaces will bring. A follow-up study after the schoolyards are ready will be able to measure changes in walkability and physical activity stimulated by the project.

The research team is working on two papers related to this project. One will offer a justification for using MAPS-Mini to understand walkability in other school renovation projects. The second paper will use before and after data from physical activity monitoring to measure the effectiveness of the schoolyard renovation on community activity. In the meantime, the walk scores we collected can be shared with the community to identify bottlenecks and problem areas impacting park access.

I look forward to seeing the completed schoolyards when they are ready, and I hope they can help Tacoma reach some of its green space and climate goals.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kathleen Wolf, Pooja Tandon, and Cary Simmons, who lead the research team, and Bernadette Labuguen, Annamarie Wire, and Eliana Cowan for their data collection. Thanks also to Quena Batres, Lily Hahn, and the ACORN team for coordinating this volunteer opportunity!

Nolan Kitts is a graduate student pursuing an MS in Environmental and Forest Sciences. His thesis research involves modeling climate change adaptation and mitigation in the Pacific Northwest’s forests.