Tackling climate change denial, one stage at a time

By Raven Capone Benko

“Climate change is happening, there’s no disagreement there. I just don’t think it’s going to be as bad as all the scientists say. I mean, look at the last fifty years since scientists started making catastrophic claims about climate change… nothing has happened.”

In my sister’s living room over cups of tea and the remnants of our white elephant gift exchange, her partner – an engineer for an oil refinery – and I were in a deep discussion about green energy, environmental ethics, and of course, the legitimacy of climate change.

The last two and a half years, I had been researching climate change denial for my master’s thesis, curious if the amplification of expert distrust sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic would bleed into other highly scientific subjects. I was initially going to track and compare denialist rhetoric on Twitter for climate and COVID-19 skeptics. But the more I read, the more I wanted to get down to the root of the issue and understand how science denialists think, why they form the opinions they hold, and how experts could better communicate to address the lack of action on climate change.

When those words came out of my soon-to-be brother-in-law’s mouth, I squealed with excitement, “How fascinating, I know exactly what kind of denialist you are!”

After several back-and-forths – me explaining various intricacies of climate modeling, ocean acidification, and climate change impacts, him advocating for the necessity of fossil fuels for society, the morality of his colleagues, and the hypocrisy of climate activists in wealthy countries whose refrigerators consume more energy than whole villages in developing countries – the conversation ended with hugs, mutual understanding, and respect. I had just had an instructive (for both of us) conversation with a member of the fossil fuel industry and saw an immediate application for my years of research. That was an amazing feeling.

WHY DO PEOPLE DENY CLIMATE CHANGE?

Science denial, like almost all problems facing our world today, is nuanced. The simplest explanation is that those who deny science don’t have the right information or a correct understanding of the information. In other words, they are misinformed. The solution – we just need to communicate with them more.

I had thought that climate change denial was a result of a lack of clear communication from the scientific community for many years. After several years in fisheries research, I mistakenly blamed the issue of scientific misinformation on a lazy scientific community. I was frustrated that research was typically only communicated through scientific articles – impossibly complicated texts often locked behind a substantial paywall. I thought, “if only scientists translated their research for a public audience and spent time actively communicating, science denial would cease to exist.” While effective science communication is extremely important, I’ve found that simply increasing the amount of information available is not end-all-be-all to address climate change denialism, but more on that later.

To truly understand the root of science denial, we must look at sources other than the quality and quantity of communication from the scientific community. In the case of climate change denial, disinformation, or the active and intentional spreading of false narratives about scientific research and environmental problems is a pervasive problem that is often funded but those who have the most to lose if climate regulations are instated; namely, the fossil fuel industry.

I heard the echoes of disinformation in the words of my sister’s partner when we debated the topic of climate change. Tactful, plausible, and sometimes scientifically supported arguments that the climate has changed in the past (true, but not at the timing and scale of what is happening now), that natural causes are the source of warming like changes in solar radiation (scientifically possible, but the last 250 years of data on solar irradiance shows either constant or slightly decreasing levels of solar activity), or there is too much uncertainty in climate models to accurately predict what may happen in the future (in fact, our climate models have actually done very well at predicting warming).

The last source, which is really a collection of sources, is a result of the individual denialist – what community do they belong to, who do they vote for, where do they live, and what do they, personally, have to lose? There are many hypotheses about the psychological underpinning for the rejection of climate change science. System Justification, where an individual is more likely to accept information that upholds the status quo, that doesn’t require change from them or their community or larger social system, is one possible explanation. Similarly, Motivated Interference, where individuals favor information that supports their personal goals, and Emotional Coherence, where people favor information that supports their values, like personal freedom or avoiding governmental interference, can dictate whether a person accepts climate change information. The list goes on.

Simply put, addressing climate change will require large scale personal, social, and global sacrifices, and humans are inherently resistant to change.

To make the explanation even more complex, opinions on climate change are also largely dependent on what community a person belongs to and how it helps form that person’s identity. Research shows that conservative white males are more likely to be climate change deniers than any other group in the US and Norway where the studies have been conducted (McCright and Dunlap, 2011; Krange et al., 2018). If your chosen political leaders deny climate change, or the dominant rhetoric in your political party or larger social group does, then it is more likely for a person to agree with their group than uphold opposing positions.

This third category(ies) interested me the most: uncovering what kinds of thinking makes a person more likely to deny climate change. But, categorizing a person under the umbrella of “climate denier” is, again, too simple of a label.

STAGES OF CLIMATE CHANGE DENIAL

Not only are there potentially unlimited sources that contribute to science denial surrounding environmental problems, but skepticism also tends to follow a loosely chronological set of stages, and a denier can be situated within one or several stages at once.

Initially, science denial focuses on data trends. For climate change, trend denial presents as people, industries, media, politicians, you name it rejecting the notion that the climate is, in fact, warming. Deniers have pointed toward abnormally harsh winters across the globe saying “see, things might actually be getting colder!”. This phenomenon is why the scientific community shifted the label from “global warming” to “climate change” in the first place.

Next comes consensus denial, a common tactic to pin experts against each other. Deniers at this stage will refute evidence on the basis that there is not a large enough scientific consensus to make a claim either way. This led to a famous study in 2013 where climate change researchers reviewed all the published, peer-reviewed literature on climate change to date and determined that 97% of scientists agreed climate change was occurring (Cook et al., 2013). It also inspired this clever skit on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver.

Deniers often then move on to attribution denial, where they attempt to blame the environmental problem on anything but human activity. The denialist argument turns to, “sure, the evidence and scientists may agree that the climate is warming, but it’s not due humans, so we don’t have to change anything”.

If a denier then recognizes that the raw data showing that the majority of scientists believe the problem is occurring and is caused by humans is legitimate, they move on to impact denial. Deniers accept that the event is occurring, but it’s not actually a problem that needs to be addressed because there won’t be large, negative impacts.

This is exactly the stage in which my future brother-in-law sat. He avidly supported that climate change was occurring, and even expressed discomfort with being categorized as a “climate change denier”. However, he resisted the idea that climate change would severely, negatively impact Earth. It’s hard to really blame him for thinking this. Amongst all the categories of climate change research, impacts are the area with the most uncertainty. Additionally, it is extremely difficult to conceptualize risks that may happen in the future and uncommon to make large personal sacrifices to benefit others if you are not the one personally experiencing the impacts of climate change.

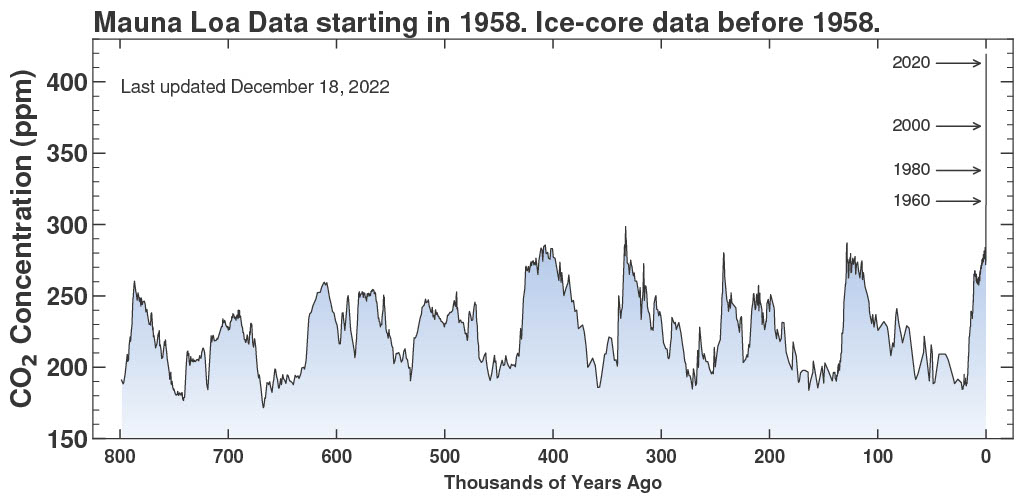

While modeling is proficient at predicting how weather patterns, ocean currents, sea level rise, and severe storms might change under climate change conditions, it becomes more difficult to predict how fish stocks, plant growth, crop yield, and various other biological systems may react. What we do know is that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is climbing at a rate never before seen in the history of life on Earth. It’s likely that organisms will have a very difficult time adapting to changing conditions. Already, science believes we are in a period of mass extinction, potentially rivaling that of the K-T extinction when dinosaurs and many other organisms were wiped from the face of the Earth.

Lastly, while not exactly a stage of science denial, climate change deniers tend to refute that any policy adopted will be efficient to address the problem without significantly harming the economy or people’s livelihoods and ways of life. I loosely named this stage as policy denial, and it is a powerful tool to stall progress on climate change policy.

WHAT CAN BE DONE

I found a renewed sense of confidence in my ability to convince people of the legitimacy of climate change when I formed a clear understanding of the sources and stages of climate change denialism. It’s an old adage, but it is essential to know your audience when communicating anything. For climate change researchers, those with an immensely complex scientific system to explain, it can be extremely helpful to understand what levels of denialism your research may run up against so you can pinpoint your communication.

If one scientist tracks changing rates of CO2 sequestration in forests and another shifts in species distributions as they travel to more suitable habitats, their work is likely to coincide with different stages of denial – the former likely with trend denialists and the latter likely with impact denialists. If you can isolate what denial source your research might overlap with and understand the stage of denial the skeptic resides in, a directed communication tactic can be found. I’ve included a simple infographic to use as a tool to understand where to situate research within the denialist landscape below.

Climate change is real, it matters, and many nations need to work to change their emissions trajectories before it’s too late. For real political change to occur, it requires buy-in from stakeholders; citizens, organizations, and industry alike; they must be convinced that action is important, and change is possible. I believe that knowing one’s denialist audience can help scientists more effectively communicate their research, as I experienced when unpacking climate change with an oil refinery engineer. There is much work still to do, but my hope is that the deconstruction of the climate denier landscape will help build empathy, understanding, and confidence when communicating climate change science.

Raven M. Capone Benko finished her Master’s in Marine Affairs from the University of Washington in December 2022. Her research focused on the public perception of climate change science, trends in climate change denial on social media platforms, and science communication writ large. This article focuses on her capstone project for the Graduate Certificate in Climate Science from the UW Program on Climate Change. She is currently working at the Smithsonian Institution as a science writer, helping to bring awareness to the contributions of women scientists throughout US history.

Raven M. Capone Benko finished her Master’s in Marine Affairs from the University of Washington in December 2022. Her research focused on the public perception of climate change science, trends in climate change denial on social media platforms, and science communication writ large. This article focuses on her capstone project for the Graduate Certificate in Climate Science from the UW Program on Climate Change. She is currently working at the Smithsonian Institution as a science writer, helping to bring awareness to the contributions of women scientists throughout US history.

REFERENCES

Björnberg, K. E., Karlsson, M., Gilek, M., & Hansson, S. O. (2017). Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015. Journal of Cleaner Production, 167, 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066

Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D., Green, S. A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., Way, R., Jacobs, P., & Skuce, A. (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters, 8(2), 024024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024

Feygina, I., Jost, J.T., Goldsmith, R.E., 2010. System Justification, the Denial of Global Warming, and the Possibility of “System-Sanctioned Change.” Pers Soc Psychol Bull 36, 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209351435

Hornsey, M.J., Harris, E.A., Bain, P.G., Fielding, K.S., 2016. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change 6, 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate294

Howe, P., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J. et al (2015). Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nature Climate Change, 5, 596–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2583

Krange, O., Kaltenborn, B.P., & Hultman, M., 2018. Cool dudes in Norway: climate change denial among conservative Norwegian men. Environmental Sociology. https://doi.org.10.1080/23251042.2018.1488516

Krishna, A., 2021. Understanding the differences between climate change deniers and believers’ knowledge, media use, and trust in related information sources. Public Relations Review 47, 101986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101986

McCright, A.M., Dunlap, R.E., 2011. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change 21, 1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003

Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J.R., Howe, P.D., and Leiserowitz, A., 2015. The spatial distribution of Republican and Democratic climate opinions at state and local scales. Climatic Change. DOI: 10.1007/s10584-017-2103-0.

Moore, F.C., Obradovich, N., Lehner, F., Baylis, P., 2019. Rapidly declining remarkability of temperature anomalies may obscure public perception of climate change. PNAS 116, 4905–4910. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816541116

Sullivan, A., White, D.D., 2019. An Assessment of Public Perceptions of Climate Change Risk in Three Western U.S. Cities. Weather, Climate, and Society 11, 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-18-0068.1

Tvinnereim, E., Lægreid, O.M., Liu, X., Shaw, D., Borick, C., Lachapelle, E., 2020. Climate change risk perceptions and the problem of scale: evidence from cross-national survey experiments. Environmental Politics 29, 1178–1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1708538

Walter, S., Brüggemann, M., Engesser, S., 2018. Echo Chambers of Denial: Explaining User Comments on Climate Change. Environmental Communication 12, 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2017.1394893

Williams, H.T.P., McMurray, J.R., Kurz, T., Hugo Lambert, F., 2015. Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change 32, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006