It’s better outside: Water and Climate Science Education

written by Oriana Chegwidden

Paper is crummy in the rain. Teenagers are listening, even if they seem distracted. An illustration of a snowman is incomplete without a stovepipe hat. A few of the lessons learned while exploring outdoor climate change education as part of my Graduate Certificate in Climate Science.

The origin story

The saga began in January 2017 when Jessica Badgeley, a graduate student in the Earth and Space Sciences department at the University of Washington, asked me whether I would be interested in being a guest scientist the upcoming summer on a Girls on Ice (GOI) Expedition to Mount Baker in the North Cascades. As part of Inspiring Girls Expeditions, GOI is an NSF-funded program which, for over two decades, has taught girls from disadvantaged backgrounds science, mountaineering, and art. They accomplish this Renaissance learning while camped for a week between the Squak and Easton Glaciers on the south side of Mount Baker. This 10,781 foot tall volcano boasts eleven glaciers which are widely seen as bellwethers of climate change and rising temperatures. The Easton Glacier, for example, lost 25% of its mass between 1990 and 2017.1 The implications of this glacial retreat for the surrounding ecosystem are profound. As the hydrologist on the GOI team, I would contribute my expertise on climate change impacts on water resources in the Pacific Northwest.

A Climate Change and Water Lesson Plan: Outdoor Edition!

With the help of Dr. Christina Bandaragoda (Civil and Environmental Engineering) I crafted a lesson which encouraged the girls to learn about hydrology and climate change by observing their surrounding landscape. We’re pictured in action on the left moraine of the Easton glacier (I’m in green).

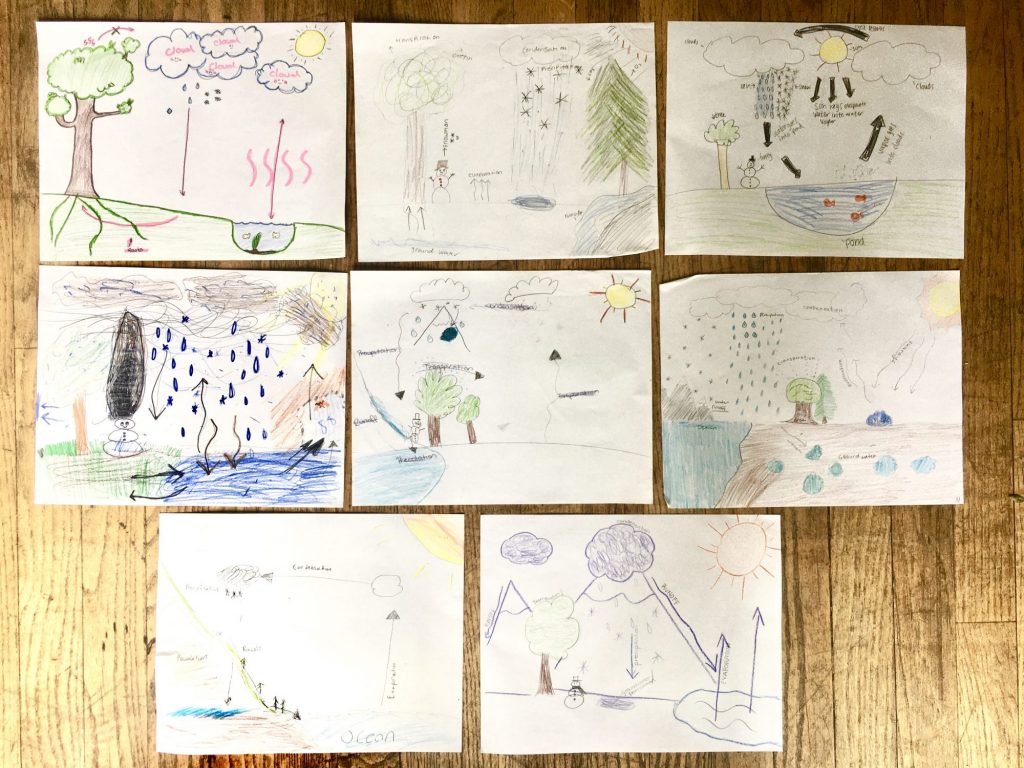

We began by drawing diagrams of the water cycle (like those in the photos below). We then postulated how the water cycle generates streamflow in rivers, and how the amount of streamflow might change throughout the year. We drew seasonal hydrographs (the standard way of plotting streamflow versus time in hydrology) to represent the behavior of streams in the recent past. Finally, we returned to our diagrams of the water cycle and speculated how climate change could impact different elements of the water cycle, and thus alter the streamflow hydrograph. They then overlaid their future projection hydrograph onto their first hydrograph to see the difference. Check out an example graph from one of the girls below. The lesson plan is available by request from the PCC.

The girls synthesized observations about their environment to make their own projections of climate change impacts on hydrology. And their graphs bore a striking resemblance to my own results born out of hours and hours of model runs on supercomputers!

The research question appears

Back in Seattle I found myself wondering to what extent the outdoor environment improved the lesson. Did the youth learn better because they were outside? Or was the learning actually worse? Research has shown that outdoor learning can promote better educational outcomes.2 And outdoor education can support hard-to-quantify attributes like cognitive development.3 Simultaneously though, when students go outside they are thrown into a host of distractions that can inhibit learning.4 With this double-edged sword, which environment fosters better learning?

I worked with Dr. Miriam Bertram, Assistant Director of the Program on Climate Change to devise a research project to answer this question. She connected me with Lori Stanton, a teacher at Canyon Park Middle School in the Seattle-area suburb of Bothell. Stanton and I planned together to deliver the lesson to two different science classrooms with one key difference: one would occur outside while the other inside. Same school, same age group, same stage in their curriculum. Who would learn better?

We created a rubric to evaluate the efficacy of the lesson in teaching water and climate change principles before and after the lessons.

Executing the plan

When I planned the lesson with Stanton, it was a sunny Pacific Northwest day in early September. I was seated next to Drumheller Fountain and had a clear view of Mt. Rainier 60 miles south. The notion of an outdoor lesson was delightful.

When I planned the lesson with Stanton, it was a sunny Pacific Northwest day in early September. I was seated next to Drumheller Fountain and had a clear view of Mt. Rainier 60 miles south. The notion of an outdoor lesson was delightful.

The weather was decidedly different in late November when I pulled into the parking lot to give my lessons. It was raining and windy. The students’ paper drawings were likely going to struggle. But the show must go on!

The lessons went off without a hitch. Stanton and I found a copse of Western Red Cedar trees to circle up in with the students for the outdoors lesson. For the indoors lesson the students gathered around lab benches, pushing aside Bunsen burners and Erlenmeyer flasks. Check out a photo from the indoors lesson above.

Both classes took time to draw the water cycle and discuss climate change impacts. The indoors group created more elaborate schematics and the outdoors group’s paper drawings suffered from the wind and rain (see photos below). Would the learning outcomes be impacted by the difficulties of the outdoor learning?

The lesson worked equally well outdoors and indoors!

There was a marked difference in the amount of detail in the drawings between indoors and outdoors lessons, a clear indicator that the outdoors class was more distracted when tasked with drawing the water cycle. However, the learning outcomes on the pre- and post- survey for the outdoors group were comparable with the indoors group, indicating that they learned well outside despite distraction. Given that there are well-documented mental, emotional, and physical benefits of outdoor education the outdoor lesson was an overall win. In other words, conducting the lesson outdoors preserved just as high a level of learning as the indoors lesson, while undoubtedly providing other benefits that we did not measure with our surveys.

The moral of the story: do your learning outside

Research shows that outdoor learning has positive impacts that reach far beyond what can be measured on a test. In this test of climate science education indoors and outdoors we showed that learning was equally successful indoors and outdoors, even on a cold, rainy autumn day in the PNW. So, if I were to recommend this lesson to a teacher, I would suggest to take it outdoors. All of the materials are available by request from the PCC: uwpcc@uw.edu.

Personal takeaways

A few final lessons learned from my side: Computers aren’t the only way to do hydrology. Distractions aren’t always a bad thing. Middle schoolers make science 100% more fun.

Oriana Chegwidden earned her PhD from the department of Civil and Environmental Engineering with the Data Science Option. The project described here contributed to her earning a Graduate Certificate in Climate Science. As a member of the Computational Hydrology group, her expertise is in the impact of climate change on water resources, with particular emphasis on policy-relevant science. Her science has been used by federal, state, tribal, and local natural resource managers and decision-makers. While at UW she also ran the water-related parts of the ClimateToolbox.org. In Fall 2020 she will begin work at CarbonPlan, a non-profit using data science to better inform carbon emissions mitigation.

2 Dillon, J., M. Rickinson, K. Teamey, M. Morris, M.Y. Choi, D. Sanders, et al. (2006) The value of outdoor learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere. School Science Review, 87 (320), pp. 107-113.

3 Eaton, D. (1998) Cognitive and affective learning in outdoor education. Dissertation Abstracts International – Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 60, 10-A, 3595.

4 Burnett,J., Lucas,K. B. and Dooley, J. H. (1996) Small group behaviour in a novel field environment: senior science students visit a marine theme park. Australian Science Teachers’ Journal, 42(4), 59–64.