What can states and their partners do about ocean acidification?

Working with the OA Alliance to map out pathways to action

Written by: Charlotte Dohrn and Hanna Miller

What do you think of when you read “ocean acidification”?

For many of us, the phrase conjures up an image of an oyster. These delicious bivalves have been the “face” of ocean acidification (OA) since the mid-2000s. While scientists had previously been aware of OA, it wasn’t until oyster hatcheries on the U.S. West Coast saw mass mortality of larvae (i.e., baby oysters) that we realized impacts had already arrived.

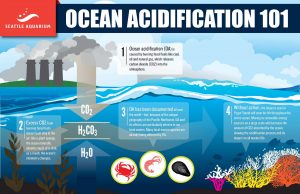

But what is OA? At a basic level, OA is a simple but invisible chemical reaction, which can make it difficult to visualize and understand. OA refers to a process where carbon dioxide (CO2) is absorbed by ocean water, setting off a chain of chemical reactions. Due to increased carbon in the atmosphere from fossil fuel burning, oceans are taking up more CO2, which drives down pH. Lower pH indicates that waters are more corrosive – and calcifying organisms, like oysters, struggle to build shells under acidified conditions.

OA affects more than oysters – its impacts are far reaching and deserve as much attention as other climate consequences, such as wildfires or sea level rise.

Our project – moving from knowledge to action

OA is often described as a global problem with local effects. The only way to truly solve the problem is to reduce global carbon emissions – though it’s also important to address local drivers like nutrient pollution. While we struggle to take international climate action, communities around the world are already facing impacts from OA. The scope and scale of the problem are daunting. While the scientific community is achieving greater certainty, policy responses are still relatively young. It hasn’t always been clear to state and regional leaders and resource managers what they can do to address OA. We jumped at the opportunity to work with the International Alliance to Combat Ocean Acidification (OA Alliance),an organization focused on taking action, for our Graduate Certificate In Climate Science capstone project.

The OA Alliance is an international organization based in Washington that focuses on motivating and empowering governments to proactively respond to OA impacts by charting a course of action to sustain coastal communities and livelihoods. The OA Alliance coordinates among members, helps disseminate the best available OA science and policy responses, and supports developing OA action plans. The Alliance members – including federal, state, regional, and tribal governments; nonprofits; and other partners – are working to study, mitigate, and adapt to OA at local and global scales. The Seattle area is a hub of OA Alliance membership and activity – not only is Washington a state member, but the City of Seattle, the Port of Seattle, and the University of Washington’s own Washington Ocean Acidification Center are also members. For our PCC capstone project, we worked closely with Jessie Turner from the OA Alliance as well as Chris Boylan, a fellow student at the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs (SMEA), and SMEA faculty project lead Eric Laschever on a project to increase communication between states and other OA players on how to respond to OA.

What did we do?

We started the project in spring of 2019, getting our feet wet in the world of OA science and policy and learning more about the OA Alliance’s work. Fast forward a few quick months, and we found ourselves in New York City, in the midst of United Nations Climate Week, supporting a workshop held in September 2019, aimed at connecting managers from different regions to discuss state-led efforts to respond to OA. We spent two action-packed days at the New York Aquarium with attendees including representatives from 13 coastal states, as well as federal agencies, monitoring networks, the shellfish industry, and nonprofit organizations.

Presenters shared the latest regional science initiatives, strategies for engaging legislators, results of pilot studies assessing localized mitigation, and more. Over lunch and breakout sessions, participants discussed the status of OA action planning in their home states, sharing best practices for carrying out recommendations from state commissioned task forces, building communication between scientists and policy makers, and overcoming challenges like lack of government support and funding limitations.

The workshop was really just the beginning of our capstone project. For the next several months, we met regularly with the OA Alliance and the rest of the UW project team to summarize and communicate the workshop outcomes. First, we synthesized the pages and pages of notes from the workshop into a concise meeting summary document that the OA Alliance provided to participants. We then worked on other products building on the conversations at the workshop, including a synthesis paper (still in development). The paper includes a process diagram that maps out pathways to action for states and their partners. Building on this work, the OA Alliance has started compiling case studies that showcase different approaches members have taken to developing OA action plans.

What did we learn?

While we both had basic knowledge of OA before starting the project, we greatly expanded our understanding of OA science and policy. We learned about how states are analyzing their OA monitoring capacity to identify gaps and add additional monitoring infrastructure in priority estuaries, efforts to co-locate water quality monitoring with biological monitoring to better understand impacts to species, and new modeling approaches that provide forecasts and will inform policy. We also learned about legislation, institutional arrangements, and action plan components that make up policy responses from coast to coast.

Through writing and presentations, we practiced communicating about climate-ocean impacts, regional research and monitoring initiatives, and how other stressors both exacerbate and provide management “on-ramps” for addressing OA. Importantly, the project provided an invaluable real-world example of knowledge-to-action – the workshop and synthesis deliverables aim to provide resources for state actors and partners to move forward in understanding and addressing OA within their local and regional waters.

We have been honored to work with the OA Alliance and our SMEA colleagues on this project. It provided a unique opportunity to attend public portions of UN Climate week and witness meaningful and honest conversations between OA managers from across the country on how they have approached OA in their states. Lastly, we are thrilled to have worked with the OA Alliance and help advance its mission. This is an important organization that is playing a pivotal role in the local, national, and global response to OA. We valued the opportunity to assist them with the workshop and help develop materials for their partners and future members.

Charlotte Dohrn is a recent graduate of the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs and completed this project for the Graduate Certificate in Climate Science. She has spent a lot of time over the years thinking about oysters – from this project on ocean acidification, to her thesis research on habitat suitability and climate considerations for native oyster restoration, to working as an oyster shucker. Charlotte enjoys working on collaborative projects at the intersection of climate and coastal science and policy.

Hanna Miller is a soon to be graduate of the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs and completed this project for the Graduate Certificate in Climate Science. While her thesis work focused on the return of humpback whales to the Salish Sea, Hanna has been interested in OA and actionable science since she was in high school. Working in coastal management following her graduation led to a desire to refocus on issues facing the ocean today. Hanna is passionate about actionable science and coastal management.