After Counting Our Summer Institute Carbon Emissions—Now What?

By Alex Stote

The PCC Summer Institute, which brings together UW climate scientists, UW grad students, and several visiting climate scholars for a 3-day conference at Friday Harbor Labs, took a critical look at its own emissions footprint for the first time in its 11-year tenure.

The exercise seemed fitting with year’s theme (Climate Change Impacts on Food and Water Security), and with the recent push-back climate scientists have received for their “business-as-usual” practices in their professional lives. By collecting information on food consumption, food waste, electricity usage and individual transport to and from the conference, Alex was able to calculate a rough estimate of the carbon footprint incurred by our gathering. Read further to hear about her motivation, her findings, and her research on carbon offsets.

Striving for net-zero: How we got there

It’s clear that we need to urgently act on the climate crisis. Business-as-usual is not going to cut it if we want to avoid severe societal disruption. And that goes for all of us. Yet as professionals who work on climate, do we not have some moral obligation to lead by example? Should we be taking the initiative to transform old behaviors into new and improved (read: decarbonized) opportunities?

This was my thought process when I approached the organizers of the 2019 Summer Institute. I suggested aiming for a “net-zero emissions” conference to signal to the scientific community, as well as the public, that behavioral changes are not only necessary, but are also possible. As we started to envision what a net-zero conference would look like, we first identified positive changes that had already been made in the last few years and searched for ways to build on those. Most notably in previous years, carpools were arranged from Seattle to and from Friday Harbor Labs (FHL). New this year, FHL removed brown bag lunches from their menu options in a successful effort to reduce waste. In addition to these measures, I worked with conference organizers and FHL to reduce meat and dairy menu options where possible, replacing those items with less emissions-intensive options such as non-dairy dips and extra vegetables.

The discussion of whether to hold this conference remotely came up briefly in the early stages of planning, but it was quickly discounted as an option because of the value of meeting in-person, which is impossible to replicate virtually. In most of its 11 years running, the Summer Institute has been held every year at FHL on San Juan Island. People in various stages of their professional careers, ranging from first-year graduate students to seasoned experts in the fields of atmospheric science, oceanography, technology, economics, communications, and everything in between, come together for 3-days of engaging discussions and exchange of ideas. The setting is what makes this climate conference unlike others. Nestled together on a quaint campus and staying in rustic cabins overlooking the ocean, participants are immersed in nature; the perfect backdrop to cultivate an intimate setting for reflection, meaningful networking, and critical discussions on climate. It was clear early on that reworking the Summer Institute into a teleconference would significantly alter its character and value for participants. So, instead, we agreed to cut emissions and waste wherever possible, and to explore the possibility of offsetting whatever we couldn’t eliminate. That’s where the carbon tracking came in. I collected data on each participants’ transportation information, the food consumed during the conference, and our electricity usage to generate a rough estimate of the Summer Institute’s carbon footprint.

Carbon accounting at the Summer Institute

This year’s Summer Institute hosted 82 participants mostly from the UW, supplemented with scholars visiting from California, Utah, and New York. Using online carbon calculators1 that specialize in different sectors, my accounting exercise suggested that we collectively emitted a grand total of 7,170.6 kg CO2 over our 3-day stay. Transportation was by far the biggest factor, contributing 6,412 kg CO2, while food consumption and waste trailed at a total of 749.65 kg CO2. Electricity emissions amounted to a mere 0.009 kg CO2e, owing almost entirely to the fact that approximately 90% of the electricity supply is derived from hydroelectric power2, a clean and renewable source of energy.

This year’s Summer Institute hosted 82 participants mostly from the UW, supplemented with scholars visiting from California, Utah, and New York. Using online carbon calculators1 that specialize in different sectors, my accounting exercise suggested that we collectively emitted a grand total of 7,170.6 kg CO2 over our 3-day stay. Transportation was by far the biggest factor, contributing 6,412 kg CO2, while food consumption and waste trailed at a total of 749.65 kg CO2. Electricity emissions amounted to a mere 0.009 kg CO2e, owing almost entirely to the fact that approximately 90% of the electricity supply is derived from hydroelectric power2, a clean and renewable source of energy.

Of the 82 travelers, 4 flew on an airplane as part of their journey and 2 arrived by float plane. Sixty-three people (about 77%) rode to and from the ferry terminals in pre-arranged carpools. Most of the carpools were non-electric vehicles and ranged in size from compact to SUV. Despite the carpooling rate, transportation emissions, including ground and air travel, averaged over 2,000 kg CO2 per day, the equivalent of burning over 2,000 pounds of coal, or driving 4,890 miles. Per day.

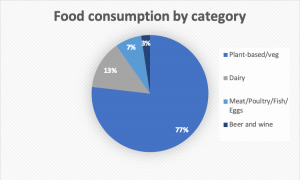

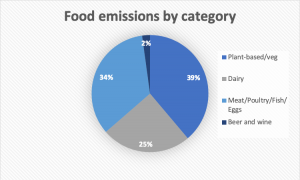

Turning to food, the greatest consumption-to-emissions ratio was the meat category (“meat/poultry/fish/eggs”) by a long shot. That is, this category made up only approximately 7% of the items consumed during the Institute, yet they accounted for 34% of the food emissions. Dairy was unsurprisingly second, constituting about 13% of the items consumed yet 25% of emissions.

The aftermath

After presenting my initial findings on the final morning of the Institute, a resounding “now what?” rang through the conversations. I had spoken with conference organizers about the possibility of purchasing carbonoffsets from the outset of this work, but we struggled to land on a final decision. I agreed to take a deep dive into the online world of carbon offsets to better understand their utility and trustworthiness. After wading through some bogus sites, I discovered that legitimate offset options do exist. Carbon-buying programs can be certified through a third-party verification system, the most popular of which appear to be the Verified Carbon

Standard, the American Carbon Registry, and the Gold Standard. Successful verification signals to the buyer that the program has met certain carbon sequestration criteria, including accounting for additionality. Offset programs and the act of purchasing offsets have each met substantial criticism, and for good reason. One of the most acute debates surrounding the purchase of offsets is that it offers an excuse for individuals and corporations to continue with “business-as-usual” behavior. If we can just offset all the greenhouse gases we emit, where is the incentive to change? Another troublesome feature about carbon offsets is their price. Lack of a strong national or international market for carbon has driven “carbon prices” so low that carbon offset prices are extremely cheap (a topic that PCC alum Naomi Goldenson has explored more in more depth in her blog). Of the legitimate programs that I discovered, the cost of carbon ranged from $8.85-15/metric ton CO2. That’s approximately $62-105 to offset our 3-day conference of over 80 participants! It begs the question—does that price truly reflect the cost of the carbon emissions?

If considering the social cost of carbon, the answer would be no. According to the EPA, the social cost of carbon “is a measure, in dollars, of the long-term damage done by a ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in a given year.” In the US, the current estimate of the social cost of carbon is approximately $50 USD; much higher than the price of carbon in offsetting schemes.

Carbon offsets are not perfect, but we must also acknowledge that, if we are not willing to make the Summer Institute a virtual conference, can we at least lower our impact? We tried doing so with the menu changes and carpool options, but the meeting still generated considerable emissions. Might it be appropriate to choose a verifiable offset program in which to invest? A different thought that emerged after the conference was that, perhaps instead of purchasing offsets, what if we rented hybrid university vehicles rather than minivans for the carpools? A quick calculation shows that doing so would cut car emissions roughly in half, from 1,400 kg CO2 to 733 kg CO2, for the total distance traveled by car. I received another suggestion that maybe all future Summer Institutes should have a fully vegetarian menu, and that meat options be available only by request— a move that would lower emissions, but still much less than eliminating flying for guest speakers.

We’re at a point where we need to change our behavior radically; buying our carbon may not be the solution. Carbon offset programs will certainly not stabilize our fragile atmospheric dynamics; we would be naïve to think they would. But still a question remains: If there are some activities, perhaps small individual actions, where we cannot eliminate greenhouse gas emissions entirely, is offsetting better than nothing? Or, a bigger and more complex question for us all to consider: What should we as a group at the forefront of the field be pushing for, and how do we intend to get there?

Alex Stote graduated with her master’s from the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs in June 2019. As a graduate student, she was actively involved in the PCC as part of the Graduate Student Steering Committee (P-GraSC, co-chair of the subcommittee of Public Engagement) and as a member of the Graduate Climate Conference 2018 Planning Committee (co-chair, Fundraising). She also completed a Graduate Certificate in Climate Science where she created a children’s board game about the impacts of climate change as her capstone project. Her research has mostly focused on the impacts of climate change on coastal livelihoods and marine food production. She currently works at Washington Sea Grant.

1 The online calculators used were: www.carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx (transportation), www.co2.myclimate.org/en/offset_further_emissions (transportation), www.resurgence.org/resources/carbon-calculator.html (transportation), www.terrapass.com/carbon-footprint-calculator (transportation), www.foodemissions.com/foodemissions/Calculator.aspx (food), and www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator (energy).

2 https://www.opalco.com/sustainability-and-the-environment/fuel-mix/